by Stefani Koorey

First published in December/January, 2004-2005, Volume 1, Issue 6, The Hatchet: Journal of Lizzie Borden Studies.

On Wednesday, October 27th, 2004, at the stately First Congregational Church on Rock Street in Fall River (across from the old Durfee high school, now a juvenile court house), I presented a lecture entitled “Lizzie and the Theatre: Theatrical Representations of the Borden Case” to an assembled crowd of approximately 40 people. Michael Martins, curator of the Fall River Historical Society, invited me to do the talk as a part of the First Congregational Church and Historical Society’s Centennial Celebration running the month of October.

October 27th, as some might recall, was also what proved to be the final game of the World Series, so we were all quite pleased at the turnout, considering we were in Massachusetts and the Red Sox seemed destined to win the series in only four games. It was also the night of a full eclipse of the moon so, as it came to pass, I shared the evening with both an historic and astronomical event.

Using Keynote, an Apple only PowerPoint type software program, the audio-visual portion of the talk included recordings of several Lizzie-related songs, video clips, and still images from both the events of August 4th, 1892 and the various theatrical mediums in which the Borden murder case is represented.

When I began my research into this area of Lizzie Borden studies I was astounded by the sizable number of instances in which this case has been portrayed on the stage, radio, and television. With the gracious assistance of my friend and fellow Bordenite Bob Gutowski, I was able to acquire copies of the play scripts, some very rare, and recordings, both video and audio, of all the other works. In addition, by searching the Internet, I also obtained multiple reviews of the remaining hard-to-find pieces—the musicals. All in all, a large collection of Bordenalia to read, view, and evaluate.

My Ph.D. is in Theatre History and Dramatic Literature (Penn State 1997), so I have a strong interest in the Borden case from this angle. I have frequently been contacted by American and Canadian producing organizations, both amateur and professional, in the course of their mounting productions of Lizzie plays with requests for resources, materials, and advice. It has been my pleasure to assist each of them in any manner that I can. Also recently, I was heavily involved in the Discovery Channel’s “Unsolved History” series treatment of the case entitled “Lizzie Borden Had and Axe,” which was broadcast October 30th, 2004.

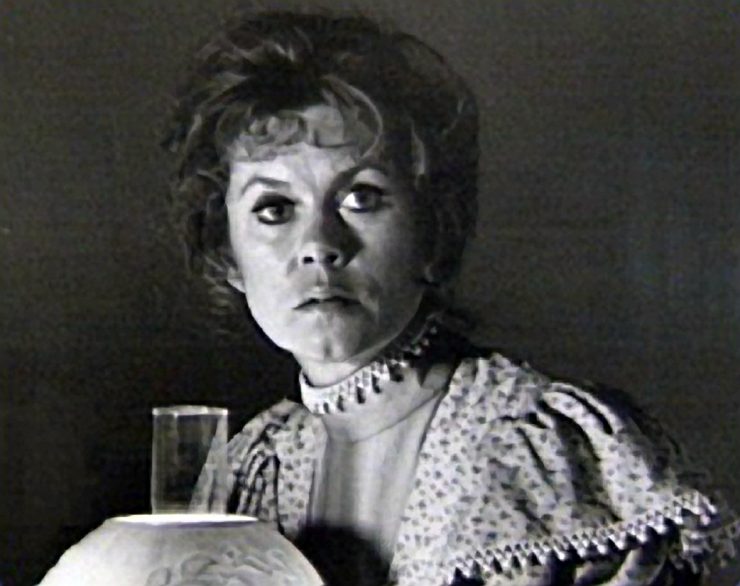

In addition, while this research project and trip to Fall River was going on, my theatre club at the college where I teach was in rehearsal for a production of Sharon Pollock’s Blood Relations, the most produced dramatic work on the case, and my personal favorite. Sharon was more than generous with her time and thoughts as we began work, and her exclusive interview on her Lizzie Borden play is included in this issue.

Apt Subject Matter?

Lizzie Borden and the murders for which she was accused, tried, and acquitted, have been represented in over a dozen stage plays, several popular songs, countless poems, one opera, one ballet, an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, a full-length television movie starring Elizabeth Montgomery, two musicals, and as many as seven radio dramas. Lizzie has also made appearances in works of art and even in cartoons, including a memorable appearance on the Halloween special of The Simpsons in 1993 as a member of the “Jury of the Damned” in the first of three Night Gallery-type stories that made up a part of “Tree House of Horror IV.” In 2002, she also appeared in the cartoon Whitehouse Weirdness in an episode entitled “Nobel Peace Surprise.”

The story of Lizzie Borden is perfectly suited for theatrical representation. Besides the fact that the murders are still unsolved and therefore fodder for grand whodunits, Lizzie remained publicly mute on the subject of the murders of her father and stepmother. Besides her inquest testimony, Lizzie never uttered one word about her feelings of being accused of the gruesome hatchet deaths. There was no death-bed confession, unless of course you believe the Ruby Cameron story [Hatchet #5], no interviews with the Fall River Herald or New Bedford Evening Standard, no diary discovered, no personal papers or letters to friends left behind to speak of her involvement, and no confession offered, the questionable Tilden-Thurber incident notwithstanding.

Add to this the Victorian sensibilities of her day when it would have been impolite to publicly discuss the murders or the woman at the center of the controversy after she was freed, especially since she remained living in Fall River to the end of her days. Oh there was gossip; there always was gossip, but in what we have come to know as the politest of societies, such discourse in the town square or to her face would have been inappropriate. This mindset still permeates Fall River, by the way, as the city itself cannot seem to come to terms with their place in infamy. While London has no problem with making a buck off its most famous Victorian crimes, and even offers tours of the Whitechapel area and Ripper death spots, Fall River is at best confused about how to acknowledge their most famous native. As unseemly as it may appear to advertise the town as the home of Lizzie Borden, they need to, in my opinion, get over this sense of propriety and allow themselves to both honor the lives of Andrew and Abby while promoting the murders as a tourist draw. After all, Lizzie was acquitted, so what can be the “official” problem with using Lizzie to help out the local economy? It feels like Fall River believes that Lizzie got away with the double murder and that is their shame—a shame that refuses to acknowledge that here once lived this woman and here once were these murders. To some Fall Riverites, I suppose, she will always be an embarrassment.

Lizzie is also quite an enigma. We really don’t know her in any personal sense. We have some stories about her life, but even those are mostly made of whole cloth. We don’t, for instance, know how the Borden’s celebrated birthdays or holidays, or the details of their daily routines before the murders. We don’t know where Emma went for that year and half when she was supposedly sent off to school. We don’t even know if Abby and Andrew were in love, although people have assumed that he married his second wife because he was in need of a housekeeper and surrogate mother to his young children.

Without this information we are left to speculate, divine, and fantasize, hopefully based on a logical or commonsense evaluation of what we do know. So it should come as no surprise that Lizzie Borden and her story would make great drama, grand opera, and entertaining moments of musical theatre. With so many blanks to fill in, the writer is free to interweave fiction with fact to craft a story that works well in the dramatic form. Lizzie is indeed the stuff of legends, and her story is worth retelling, again and again.

It’s a Family Affair

The most intense theatrical dramas are about families. Unlike film, which is what I call a passive form because it does not demand that you interact with it to make it work, theatre is a living, breathing thing that requires a live audience to bring it to life. Plays typically contain only two main characters—designated as the protagonist and antagonist. The protagonist is the character who changes and the antagonist facilitates that change (only in the most simple form of drama, the melodrama, will you find the stereotypical good guy/bad guy division between these roles). Theatre succeeds as an art form by making the audience want to follow a character through their trials and tribulations until the protagonist finally realizes his true self and learns a lesson or two about life. It is from identifying with this character growth that the audience finds satisfaction.

That is why in dramatic works for the stage the protagonist and antagonist will most often be related to one another. Just as in real life, it is family members who know how to push those emotional buttons and force one into facing themselves squarely. As I describe to my students, if a total stranger walks up to you and tells you that your haircut is ugly, your reaction will most likely be to disregard this comment as some sort of odd or rude behavior on the part of the person sharing their opinion with you. But if your mother makes the very same unsolicited remark to you, then that comment has substantial weight and is taken to heart.

A short list of plays which illustrates my argument about the effectiveness of family drama and the importance of the protagonist and antagonist being related to one another are: Oedipus Rex, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, King Lear, Long Day’s Journey into Night, The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, Death of a Salesman, and A Raisin in the Sun. Now lets look at the Borden family and see if they qualify as the same type of theatrical subject matter.

The Bordens were a close-knit family unit, this we know for sure. Their closeness, or rather, their closed-off-ness is what works to make their story so rife for debate and so inspiring of controversial readings of their private lives. What exactly happened in that house, between those people, and when and why did it all disintegrate into murder? Also, there are no direct heirs to protect or speak for the Borden sisters—the lineage ending with the passing of Emma, some nine days after Lizzie in 1927. Add to this the various side issues that writers and Bordenphiles have inserted into the story (incest, lesbianism, child abuse, greed, and kleptomania), most without any factual substantiation, and you have the makings of a complex family dynamic, ideal for the stage.

Did She or Didn’t She?

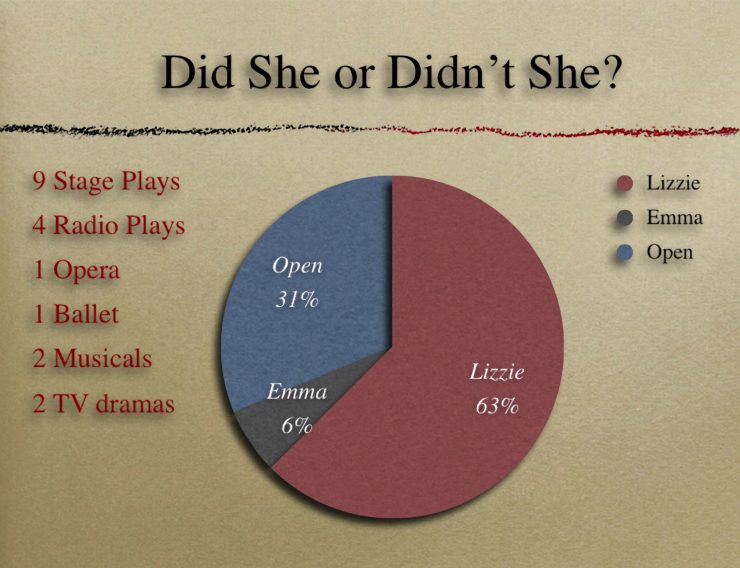

In the course of my research I examined a wide variety of works “starring” Lizzie Borden (see end notes for list). Initially, I was interested in who these writers thought had committed the crimes. I created a pie chart to show this breakdown.

Most of these playwrights have chosen to sport a “Lizzie did it” theme. Almost all others leave the identity of the perpetrator up to the audience to decide. Included in this category are those playwrights who lean heavily on Lizzie as the killer, but stop short of naming her in any specific way. There is but one writer, Lillian de la Torre, who names Emma as the murderess. Interestingly, hers is the singular work that has been produced as a stage play, a radio play, and a television drama. In each incarnation, the culprit is clearly stated as a psychotic Emma who Lizzie has hidden from the world, both sisters still living in the same house in which the murders took place.

The motives that the “Lizzie did it” authors give are varied but there is a through line or common thread that links them all together. In every case, whatever Lizzie’s motive for the savage killing of her father and stepmother, it is justified and the old folks got what was coming to them. I think that this need to find a method to her madness stems from the American belief that our legal system works to convict the guilty and acquit the innocent, that nobody truly gets away with murder or profits from their crimes. It is as if the idea of justice is so sacred to us that we cannot accept or allow ourselves to think that this woman tricked the system and lived happily ever after. So if she did it, as those playwrights depict, then she cannot be a cold-blooded killer or psychopath/sociopath, but a victim through and through. Isn’t it a shame that the real victims of this case are so maligned as to make them seem deserving of their fates? And yet, it is more dramatic, and hence, more theatrically interesting and suspenseful to craft a killer who has no other choice but to hatchet murder her parents.

Representations

Without overloading the reader with synopses of all the plays on the case, I have, instead, chosen to include several of the most interesting and well written, providing you with a taste of what exists rather than detailing the entire oeuvre. Several of the works are also, unfortunately, deadly dull as far as theatre pieces go. These ill-conceived works rely too heavily on actual testimony as the basis for their storytelling, and thus take a highly dramatic event loaded with passion and intrigue and reduce it to a presentational work of courtroom drama—actually more suited to being a radio play than a stage play.

Speaking of radio plays, I listened to quite a few and was fascinated by the way each one used voices and sound effects to convey the atmosphere of that household and Fall River in 1892. These radio plays, by necessity, are quite basic in their construction, lasting less than one hour and having only a few characters. This simplicity makes sense when you immerse yourself in the medium of the radio play, where your number one job as an audience member is to truly listen to the action instead of watch it. The writers of such pieces have to craft a story that can be easily followed without pictures or characters who can be differentiated by their appearance. Specific and memorable vocal characterizations are the secret of good radio plays, but, unfortunately, with our modern sensibilities, these same strengths can be seen as weaknesses, as the characters are reduced to primitive stereotypes.

It is interesting to note that none of the dramatic works I studied, with the exception of the Elizabeth Montgomery TV movie, showed the murders taking place. One reason for this is that it is extremely difficult to authentically portray a killing in a live production, especially the hatchet murder of two people. The risk is that it will not be convincing, thus ruining the climax of the story. If done improperly and without the right amount of verisimilitude, the audience may actually laugh at the attempt, producing the exact opposite reaction than that which is intended. Instead, in all of these works where the murders occur, their authors have elected to have the violent acts take place off stage. There is quite a precedent for this in the theatre, by the way, the idea being that you, the audience, will probably imagine a much more gruesome event than any that could ever be staged.

Gave Her Father Forty Whacks

And that brings me to my own quandary. I love the made-for-TV movie, have fond memories of being terrified when I first saw it, and think Elizabeth Montgomery’s performance first rate. But what I must also acknowledge is that the movie’s vivid portrayal of both murders has done more to damage the study of the case than any inaccurate book, article, or play. Because film is a visual medium, the images of these acts are forever imprinted on the minds of anyone seeing them. In a sense, The Legend of Lizzie Borden has locked down the scenes of the deaths of Andrew and Abby in the most explicit and provocative manner possible, thus ruining our chances to use our own imaginations. Lizzie’s orgiastic killing of Andrew is shown in slow motion, intercut with snippets from previous scenes of their lives together. It is a fulfilling of both character’s destinies to show Lizzie, the virginal daughter, violently slay her emotionally betraying father while she is naked. She even calls his name and waits for him to see her sans garments before she lets him have it, releasing some primal need to destroy, nay obliterate, the man who created her.

The ballet, Fall River Tragedy, also uses sexual inference in regards to the killings when it shows the Lizzie character dancing around a full-sized axe that has its head buried in a large stump of a tree. She is both attracted to this phallus symbol and repulsed by it, circling it, caressing it, running away from it. The little handleless hatchet that was produced at the trial as the possible murder weapon has now become a possible lover, and a definite avenue of liberation from the confines of her father’s imposed prison of a house on Second Street.

The opera version of the story, Lizzie Borden: A Family Portrait in Three Acts by Jack Beeson, uses a similarly enormous axe, which Lizzie carries up the stairs to the off stage murder room with loving care. Beeson has his Lizzie commit both murders, not in the nude, but in her mother’s wedding dress. Following the killing of Abby, Lizzie sings about how she and her father can now be alone together, much like a bride and groom. It is only when Andrew realizes and is appalled by what Lizzie has done that she decides to kill him too. The opera ends with an empty stage, immediately after Lizzie has once again ascended the stairs, this time to take the life of her father/husband.

Nine Pine Street

The first play written and produced on the case was Nine Pine Street in 1934 by John Colton and Carlton Mills. It starred the great Lillian Gish, star of the silent screen and professional theatre. A portion of the New York Times review follows:

Of special note is the “Story of the Play” essay that appears in the acting script of Nine Pine Street. It is too outrageous to paraphrase so I include it here in its entirely:

About forty years ago Fall River, Massachusetts, was just a little New England town, steeped in New England traditions. In all probability few people had ever heard of it and certainly fewer people cared. And then suddenly it was the most famous town in the United States and the most inconspicuous citizen—Miss Lizzie Borden—was the most famous woman in the country.

Delving back into old newspapers, our research showed that Miss Lizzie Borden was in love with a young minister. On the day that she had made up her mind to promise to marry the young man her father came home with a bride. Lizzie was furious, because her mother had been dead but a few weeks. Right then and there she refused to marry the minister and continue to live at her father’s home, doing all she could, in her sweet, sympathetic, religious way, to make life miserable for the step-mother. Finally the day came when she accused that woman of having killed her mother. It would seem that the mother lay ill with heart trouble. There was a small amount of the medicine on the table—the only thing that would help her. And this stepmother, visiting the house at the time, knocked the bottle over on purpose, and as a result the mother died. Lizzie had harbored this in her heart for a long time, and when she finally flung the accusation at the stepmother—words and insults flew thick and fast. The lid boiled off the placid New England Lizzie, and armed with an axe she furiously and determinedly beat the life out of the intruder, and when her father protested—she sent his soul along the same path.

She was tried, and in a trial that lasted ten months was finally acquitted. The country had taken sides—bets were laid—and opinion given willingly and scathingly. Lizzie retired to her Fall River home and lived there, without companionship or love, until she died in 1927.

The authors have changed Lizzie’s name—they call her Effie Holden—but if you’re at all acquainted with the story you’ll recognize the famous Borden Murder Case, and if you’re not familiar with it you’ll be glad to make its acquaintance.

The play is written in neoclassic five act structure, with an added epilogue that presents the Lizzie character twenty years later. For some reason, the play gives the date of the murders as August 1887 and has Lizzie (Effie) as the older sister. The playwrights also make her uncle Morse into a sea captain, her mother dying when Lizzie is an adult with Andrew remarrying two weeks later, and shows the murders as happening in quick succession. After the murders, Lizzie continues to live in the house. All in all, a fanciful retelling of an easy to research historical event!

Goodbye, Miss Lizzie Borden

Lillian de la Torre’s 1948 one-act was the second play written and produced on the Borden case. The action takes place at the scene of the crime, where Lizzie and Emma had “shut themselves up” together, on the one-year anniversary of the murders. At least de la Torre honestly includes a disclaimer that her play “fictitiously portrays the show-down which places one of the sisters in deadly peril and parts the two forever.”

I liked this play a lot, despite the character of Nellie Cutts, a fast-talking, bossy, and thus mannish, reporter from California, who pushes her way into the house in search of an exclusive. I like that the play has only four characters—all female. I like that it is a short work and thus economical in form and content. But the best thing Goodbye, Miss Lizzie Borden has going for it is that it has a great plot twist at the end that you don’t see coming.

The play begins as Emma has decided to leave the house forever. As she tries to sneak out, she is caught by Maggie who reasons that she doesn’t want to be left living in the house alone with the “strange” Lizzie Borden, and also wants to leave for good. Lizzie is portrayed in the conversation between Emma and Maggie (called exposition in theatre terms) as forever spying on the women. They express fear of her, saying that Lizzie gives them the “shivers.” Apparently, one of Lizzie’s habits is to stand perfectly still and stare blankly into space, almost trancelike. In the year that has passed since the murders, Second Street has had no callers or parties, prompting Maggie to remark that they live in a “house of death.”

Enter the pushy newspaperwoman from the Sacramento Record, looking for her exclusive. She questions the women rudely, asking personal questions about their fear of living with Lizzie and whether or not there is insanity in the Borden family.

Lizzie enters from upstairs, after obviously listening to their goings on. She informs Emma that she talks too much and orders her upstairs. Lizzie then ejects the reporter from her house. Alone in the room and reminded of the events of the year before, Lizzie uses a poker to open a secret panel near the fireplace. She reaches her arm in and pulls out a bundle—the hatchet wrapped in an apron spills out.

Emma comes downstairs saying she missed her train, catching Lizzie with the incriminating evidence in her hands. Lizzie admits to Emma that this was their father’s hiding place, his secret keep for his money and she had witnessed him using it when she was a child. Then comes the twist! It is not Lizzie who murdered Andrew and Abby, with Emma protecting her, but the exact opposite. Emma did the deed and used Lizzie’s apron to shield her from the splattering blood. Apparently, Emma hated Abby ever since she came to their family and was especially angry with Andrew for marrying so soon after their natural mother had died. It was Emma who laughed on the stairs that morning as Maggie was trying to open the front door locks and let Mr. Borden in. The exchange about the murders is riveting and very well written.

LIZZIE: . . . How do you know what I went through? The crowds staring at you thinking you did it—the women who hiss you at the courtroom door—they want so see you dead. What do you know about it?

EMMA: What do you know about it, Lizzie? You had the easy part. You didn’t have to do it. I thought it would be like chopping wood. It isn’t. Wood splits. Flesh . . . Flesh strikes back. It stops you. You feel the resistance all the way up to your elbow. And wood doesn’t bleed. Blood . . . Blood doesn’t flow, Lizzie. It flies. It jumps at you. The air is red with it.

Emma then loses her grip on reality as she relives the murders. She picks up the hatchet and appears ready to kill Lizzie when all is saved by the reappearance of the nosey newspaperwoman. Lizzie quickly gets Emma out of the room. But the reporter has figured it out and vows to expose Emma as the murderer. Lizzie then admits that she did the crimes. When asked her motive she wryly replies, “I don’t like cold mutton soup.”

Lizzie tells the reporter that she cannot print her confession or she will sue her. She threatens her with the hatchet and the formerly fearless woman runs out of the house crying for her life. The play ends with Lizzie wielding the hatchet and striking it into the table, as she remains on stage alone, contemplating her future with Emma.

If you want to see a faithful version of this play, I highly recommend the episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents called “The Older Sister.” It can be found from time to time on eBay as a collectable and is a great Lizzie item to own.

The Lights are Warm and Colored

While an odd name for a play about Lizzie Borden, this work by British playwright William Norfolk is a great piece of drama. It is not only factually accurate in terms of the crimes, but is also well written and especially evokes the crime’s time and place in a unique fashion. I like that the work is highly theatrical, with the action of the script a play within a play. It nicely fits to have a stage play use elements of theatre to help tell the story.

Lights opens in 1905 at Maplecroft, several years after Lizzie’s acquittal, and just before Emma’s departure. Lizzie has invited some players from a visiting touring company to the house. Being curious, they are very interested in the truth of the murders and, being actors, reenact the circumstances of the crime. During the course of the evening, Bridget returns to Fall River, breaking into Maplecroft through a window. She has run out of the money Lizzie has given her and wants more. We never do find out if this money was to keep Bridget quiet, out of the way, or payment for a hit on the old people. The author prefers an open-ended reading of the events of August 4th, 1892, and the audience is not disappointed or let down by this enigmatic close.

Lizzie!

If you want to read a serio-comedy on the case, I recommend Owen Haskell’s Lizzie! It is full of double entendres, puns, and jokes that only someone very familiar with the case will catch. I especially liked the character of Bridget who spends the play muttering insults under her breath, getting caught, and ingeniously rewording her comments to appear less rude. There is also a running joke about the mutton soup that really adds spice to this tongue-in-cheek play. The final line perfectly sums up the style of the piece and the attitude of the playwright when he has Lizzie say, “There’s nuttin like mutton!” ‘Nuf said, I think.

Blood Relations

Sharon Pollock’s play about the Lizzie Borden story has enjoyed a long and successful stage life. Written in 1980, both amateur and professional theatre groups have produced it worldwide. Blood Relations most effectively uses the medium of theatre to tell its tale. The play begins in 1902 at 92 Second Street with a lone actress (Nance O’Neil?) on the stage trying to remember her lines. Enter Lizzie Borden, insinuated only to be romantically connected to this woman who is practicing her craft in her house. The actress asks Lizzie if she did it, to which Lizzie responds by inviting her to find out for herself by doing what she does best—act out the circumstances of that infamous August day. Lizzie Borden then assumes the identity of Bridget Sullivan and the Actress becomes Lizzie Borden. We are taken to what Pollock calls the “dream thesis” time of 1892 and the events surrounding the murders unfold. The Actress/Lizzie learns first hand how miserable her existence was in a family where her father has shifted allegiances to his nagging wife, where that same wife’s brother is conspiring to take over ownership of Lizzie’s beloved farm in Swansea, and where her sister Emma would rather not get involved in the bickering and refuses to take her side. Abandoned and alone in this house full of big personalities, Lizzie decides that the only avenue of escape is to kill her father and stepmother. She selects the hatchet as her murder weapon because it was the same instrument of death that Andrew had used when he killed her pet pigeons.

Psychologically complex and uniquely told, Blood Relations is a brilliant work of dramatic literature and a remarkable theatrical telling of the Lizzie Borden story. Both sympathetic and pathetic, the Actress/Lizzie is inexorably drawn into the past to find the answer to her question of her friend’s guilt or innocence. She unexpectedly finds that she too would have responded to the situation the same way Lizzie did. By using an outside character to discover this personal truth it makes this story a stronger and more satisfying examination of both the members of that household and the circumstances that worked to create the “need” to choose murder over madness.

Lizzie, Theatre, and Reality

We know so little about the historical Lizzie Borden. For those who study the case and wish to theorize as to the actual happenings on August 4th, 1892, this lack of concrete knowledge is a source of great frustration. If we don’t know the details of the Borden family dynamics, we are left with supposing and working with possibilities instead of facts. At best, we can hold an informed opinion, which is a long way from certainty. The playwright, on the other hand, thrives on this same lack of specificity, using the blank slate that is Lizzie Borden as a springboard for all sorts of creative and emotionally satisfying depictions. Perhaps Lizzie is, finally, the stuff of dreams and can never be flesh and blood to us in any real way. By her very silence, Lizzie has forbidden us to come close to her, keeping us all at some ironic arm’s length. Knowing her love of the theatre, we can guess that Lizzie Borden would probably appreciate to a greater degree the myriad of plays written about her than any of the other attempts to decipher her life—especially since all of the playwrights who have had a go at her story find her acquittal morally justified.

End Notes:

Plays:

Nine Pine Street (1934), by John Colton and Carlton Mills

Goodbye, Miss Lizzie Borden (1948), by Lillian de la Torre

The Legend of Lizzie Borden (1959), by Reginald Lawrence

Lizzie Borden of Fall River (1976), by Tim Kelly

The Lights are Warm and Colored (1980), by William Norfolk

Blood Relations (1980), by Sharon Pollock

Lizzie! (1993), by Owen Haskell

Slaughter on Second Street (1993), by David Kent

Miss Lizzie Borden Invites You to Tea (1995), by Marjorie Conn

The Fall River Axe Murders (2003), adapted from the short story by Angela Carter

Radio Plays:

The Trial of Lizzie Borden (1945)

Fall River Tragedy (1952)

The Bloody, Bloody Banks of Fall River (1953)

Goodbye, Miss Lizzie Borden (1955)

Opera:

Lizzie Borden: A Family Portrait in Three Acts (1965), by Jack Beeson

Ballet:

Fall River Legend (1948), choreographed by Agnes de Mille, music by Morton Gould

Musicals:

Lizzie Borden: The Musical (1998), by Christopher McGovern and Amy Powers

Lizzie: A Musical Tragedy in Two Axe (1995), by Michael Wanzie and Rich Charron

Television Dramas:

The Older Sister (1956), an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, based on her one-act play Goodbye, Miss Lizzie Borden (1948), by Lillian de le Torre

The Legend of Lizzie Borden (1975), made-for-TV movie starring Elizabeth Montgomery